Philip II of Macedonia (382-336 BC), king of Macedonia (359-336 BC), son of Amyntas II and Eurydice was born in Pella, the capital of ancient Macedonia. During his childhood he saw the Macedonian kingdom disintegrating while his elder brothers Alexander II and Perdiccas III, fought unsuccessfully against insubordination of their regional vassal princes, continuous attacks by the northern Greek city Thebes, and invasion by the Illyrians of the northwest frontier. Also, before Philips’s rise, the ancient Macedonians regarded the ancient Greeks as potentially dangerous neighbors, not as kinsmen, and similarly, the Greeks viewed the Macedonians as barbarians (non-Greeks), and consequently treated them in the same manner in which they treated all non-Greeks. For instance, Herodotus, relates how the Macedonian king Alexander I (498-454 BC), the Philhellene (that is “a friend of the Greeks” and thus a non-Greek), wanted to take a part in the Olympic games. The Greek athletes protested, saying they would not run with a barbarian. Similarly, the historian Thucydidis also considered the Macedonians as barbarians.

Olympia, mother of Alexander the Great

Philip II of Macedonia, father of Alexander the Great

Philip II was a hostage in Thebes, from 370 BC to 360 BC. During that period he observed the military techniques of Thebes, where the great tactitian Epaminondas was in charge. Before Philips arrival, Thebes defeated a Spartan army at Leutra (371 BC), which was by a series of successful expeditions into the Peloponnese (370-369, 369-368, 367, and 362). Thus, Thebes put an end to the military dominance of Sparta, firmly establishing itself as the biggest military power in Greece. Philip made great use of his stay in Thebes as he later reorganized the Macedonian army on the model of the Theban phalanx. In 364 BC Philip returned to Macedonia, and in 359 BC he was made regent for his infant nephew Amyntas, the son of his brother Perdiccas III. Soon he seized the throne for himself, suppressing foreign and Macedonian opposition.

Philip came to the throne suddenly and unexpectedly in 359 BC, after his brother Perdiccas III was killed together with about 4000 of his troups meeting an Illyrian invasion (Diod. 16.2.4-6). The situation in Macedonia was grave. In this moment of crisis, Philip persuaded the aristocrats to recognize him as king in place of his infant nephew, for whom he was now serving as regent after the loss of the previous king in the field. Philip then rallied the army by teaching the infantrymen an unstoppable new tactic (Diod. 16.3.1-3). Macedonian troops carried thrusting spears fourteen feet long, which they had to hold with two hands. Philip drilled his men to handle these heavy weapons in a phalanx formation, whose front line bristled like a lethal porcupine with outstretched spears. With the cavalry of aristocrats deployed as a strike force to soften up the enemy and protect the infantry’s flanks, Philip’s reorganized army promptly routed Macedonia’s attackers and suppressed local rivals to the new king.

The Illyrians prepared to close in as the Macedonian state was further weakened by internal turmoil; additional claimants to the throne were a serious threat to Philip’s dominance, since they were supported by foreign powers. Philip used the crisis as a great opportunity to demonstrate his diplomatic skills. He bought off his dangerous neighbours and, with a treaty, ceded Amphipolis to Athens. In less than two years he secured the safety of his kingdom and firmly established himself on the throne. After defeating the Illyrians in 358 BC, Philip sought to bring all of Upper Macedonia (especially Lynkestis, the birthplace of his mother) under his control and make them loyal to him (Isoc. 5.21; Diod. 16.3.4-7; Diod. 16.4.2-7). Apart from military, Philip had several political inventions that helped turn Macedonia into a world power. His primary method of creating alliances and strengthening loyalties was through marriage. In 357 BC he married Olympia, from the royal house of Molossia, and a year later they had a son, Alexander.

Marble head of Alexander The Great.

But Alexander never got along well with his father, although Philip was very proud of his son Alexander, as seen in the the Bucephalus incident. Alexander had always been closer to Olympia than to Philip. This, in addition to a number of other reasons, was the reason why Philip and Olympia did not get along all that well.

Philip allowed the sons of nobles to receive education in the court of the king. Here the sons would not only develop a fierce loyalty for the king, but it was also a way for Philip to, in a sense, hold the children hostage to keep their parents from interfering with his authority. He also gave more people positions of power and more of a sense of belonging to the kingdom.

Philip’s policy, while being very tactful, was also aggressive. In 357 BC he conquered the Athenian colony of Amphipolis in Thrace. That gave him a possession of the gold mines of Mount Pangaeus, which will finance his wars. In 356 BC he captured Potidea in Chalcidice, Pydna on the Thermaic Gulf, and in 355 BC e Thracian town of Crenides, later acquiring new name Philippi. In 354 BC Philip conquered Methone, advanced into Thessaly but did not attempt to take the pass of Thermopylae in 352 BC because it was strongly guarded by the Athenians. By 348 BC Philip had annexed the Chalcidice, including Olynthus, and was involved in a war over Delphi between Phocis and its neighbors. His aggressive politics got him as part of the settlement (346 BC) Philip a seat in the Delphic council, with a recognized position in Greece. However, this policy did not sit well with the great Athenian orator Demosthenes, who in 351 BC delivered the first of his Philippics, a series of speeches warning the Athenians about the Macedonian menace to Greek liberty. The Philippics (the second in 344 BC, the third in 341 BC) and the three Olynthiacs (349 BC), in which he urged aid for Olynthus against Philip, were all directed toward arousing Greece against the conqueror. Philip wanted to be acceptable in Greece — after all, Isocrates had advised him at this time that he needed to involve the Greeks with the Persian war — and the Philipics weren’t helping him. His philhellenism was a key strategy of the great tactitian. He respected Athens for diplomatic reasons, but he never in his life set foot in Athens. Furthermore, Pella had been a resort or refuge of great Greek thinkers, a curiosity given that there is no indication that he was truly a man of the arts and humanities. His philhellenism was tollerated due to Macedonia’s military strength, although it was well-known that it was not genuine and overrated; and Demosthenes knew how to use it. In the third of the Philippics, generally considered the finest of his orations, the great Athenian statesman spoke of Philip II:

“… not only no Greek, nor related to the Greeks, but not even a barbarian from any place that can be named with honors, but a pestilent knave from Macedonia, whence it was never yet possible to buy a decent slave.”

Third Philippic, 31

Demosthenes continued to agitate, and when Philip moved to absorb the European side of the straits and the Dardanelles (340 BC), Athens and Thebes went to war with him. The Macedonian barbarian defeated the united Greek states at the battle of Chaeronea at the beginning of August 338 BC and appointed himself “Commander of the Greeks”. Philip’s army was outnumbered by the Athenian and Theban forces, yet his phalanxes overwhelmed the Athenians and Thebans. This battle was followed by the establishment of Macedonian hegemony over Greece.

The winner of the Battle at Charonea won the war. Philip now secured peace with the Greeks, and with that their support in the Persian war overseas. It is believed that Aristotle helped him greatly in the constitutional details of his settlement, as he was not tutoring the young Alexander anymore. Philip’s League of Corinth (337 BC) was intended to maintain and perpetuate a general peace (koine eirene); it was not a league at all, for it did not have the word symachia in it. The Council (synedrion) included delegates of all the states of Greece (except Sparta) and the islands, recognizing Philip as its leader (hegemon). The peace was a political innovation of the Greeks themselves, used several times in the past 50 years; neither Philip nor Macedonia had representatives on the council, though. Philip was extremely wise to build on the earlier practice of the Greeks themselves. However, the catch was that the hegemon influenced the decisions of the council, and was responsible for their execution. This facade of freedom, did not deceive the Greeks. After all, it was quite obvious why the inaugural meeting took place in Corinth, for it was one of only few Greek cities with a Macedonian garrison; the other were strategically positioned at the Theban Cadmeia, Chalcis on Euboea and Ambracia. Therefore, Philips’s settlement of Greece was only a means for his future plans.

The synedrion duly acclaimed Philip’s idea for a Persian war early in 337 BC. Early the next year, in the spring of 336 BC, Philip started preparing for his big invasion of Persia. He sent Attalus and Parmenion with 10,000 troops, an advance force, over into Asia Minor.

Two years before this, the great diplomat made, what is believed to be, the most incompetent mistake of his life. His last marriage, in 338 BC, to the Macedonian Cleopatra, led to a final break with Olympia, his queen, who left the country accompanied by the crown prince Alexander. At the wedding banquet, Cleopatra’s father made a remark about Philip fathering a “legitimate” heir, i.e., one that was pure Macedonian. Alexander took exception and threw his cup at the man, and some sources say Alexander killed him. Enraged, Philip stood up and charged at Alexander, only to trip and fall on his face in his drunken stupor. Alexander, rather upset at the scene, is to have shouted:

“Here is the man who was making ready to cross from Europe to Asia, and who cannot even cross from one table to another without losing his balance.”

Philip miscalculated how much this marriage was going to harm his relationship with Alexander. Philip showed that he had never intended to put Alexander’s position as crown prince in jeopardy, by taking trouble to be reconciled with Alexander. Still, once Philip divorced Olympia Alexander fled. Although allowed to return, he remained isolated and insecure until Philip was assassinated, in the summer of 336 BC.

At the grand wedding celebration of his daughter Cleopatra’s marriage to Alexander of Epirus (brother of Olympias), Philip was assassinated by Pausanias, a young Macedonian noble. The official explanation was that Pausanias was driven into committing the murder after he was denyed justice by the king in a bitter grievance against the young queen’s uncle Attalus. Pausanias himself could add nothing to it, as he was killed on the spot. Not surprisingly though, rumors came up that Olympias and Alexander were involved in the assasination — that they used Pausanias’ anger to further their cause — as they had most to gain from Philip’s death. Few years later, however, Aristotle used this incident in his work Politics as an example of a monarch murdered for private and personal motives, hinting at what the prevailing public oppinion was like at the time.

His vision to conquer the Middle East, will be carried away by his son Alexander the Great. However, without the military and political efforts of Philip, Alexander would have never been as successful. After all, Philip was the true founder of Alexander’s army, for he trained some of his best generals, such as Antigonus Cyclops, Antipater, Nearchus, Parmenion, and Perdiccas. According to Bosworth, Philip’s work with the Macedonian army and establishment of alliances with the Balkan peoples gave both himself and Alexander the resources necessary to carry out such conquests.

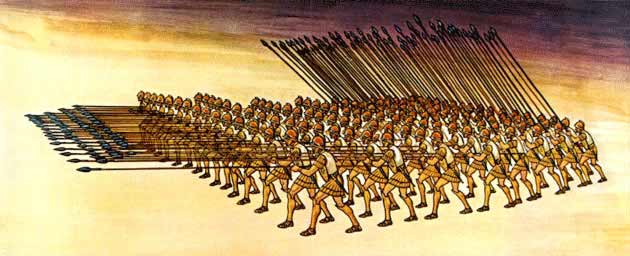

A drawing of the Macedonian phalanx, designed by Philip II, a basic factor in the military achievements of the Macedonians.

Philip introduced the 6 meter (about 18 feet) long sarissa, a wooden pike with metal tip, for use by his infantry in the phalanx. The sarissa, when held upright by the rear rows of the phalanx (there were usually eight rows), helped hide maneuvers behind the phalanx from the view of the enemy. When held horizontal by the front rows of the phalanx, it was a rather brutal weapon. People could be run through from 20 feet away, giving quite an advantage to the phalanx in hand-to-hand combat.

Philip made the military a way of life for many Macedonian men. He made the military a professional occupation that paid well enough that the soldiers could afford to do it year-round, unlike in the past when the soldiering had only been a part-time job, something the men would do during the off peak times of farming. This allowed him to count on his man regularly, building unity and cohesion within the army. In addition to the basic phalanx, Philip and Alexander used light auxiliaries, archers, a siege train, and a cavalry.

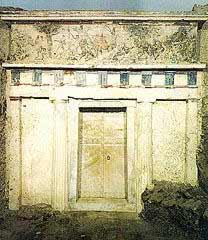

The royal tomb excavated in 1977 at Vergina, near Salonika, was at first believed to be Philip’s, only later to be proven that it dates from around 317 BC, suggesting that the tomb belongs to King Philip III Arrhidaeus, bastard son of Philip II and a female dancer, Philinna of Larissa, and half-brother of Alexander the Great (Science 2000 April 21; 288: 511-514). Philip III could not match the leadership skills of his father and his half-brother. On the death of Alexander the Great he was elected king under the name of Philip III by the Macedonian army, and in 322 BC he married. On their return to Macedonia he and his wife were made prisoners and put to death by order of Olympia, in the year 317 BC.

The Macedonian kings continued to exercise their sovereignty over Greece until the conquest of Perseus by the Romans in BC 168, which brought the Macedonian monarchy to a close.

Virtual Macedonia

Republic of Macedonia Home Page

Here at Virtual Macedonia, we love everything about our country, Republic of Macedonia. We focus on topics relating to travel to Macedonia, Macedonian history, Macedonian Language, Macedonian Culture. Our goal is to help people learn more about the "Jewel of the Balkans- Macedonia" - See more at our About Us page.

Leave a comment || Signup for email || Facebook |

History || Culture || Travel || Politics