OOne of the major, long-standing questions confusing the historical record has been the question of state legality and legitimacy of the kings of Prilep. The contemporary Serbian historiography proved that the long-time governing notion regarding Volkashin’s (and Uglesha’s) act of “usurping” and “tyrannical” act of assuming the king’s (and tyrant’s) crown was untenable. Although data on the origin of the King Volkashin and his son Marko are extremely insufficient and unsure, it is indisputable that they have arisen from the hierarchy of the Serbian feudal state. However, it is indisputable that there were state formations which were opposed to the north Serbian states, and were not even close to the eastern Bulgarian kingdoms in Macedonia in the 14th century.

On April 15, 1345, when the Serbian king Dushan was crowned as Tsar in Skopje, almost the entire territory of Macedonia was within the scope of his large state, and individual parts were governed by feudal vassals of high rank. Ten years later, after the death of Tsar Dushan (1355), his kingdom began to fall apart – due to, among other causes, intensified strivings of the feudal lords for greater independence. It is believed that the process of the establishment of independent states and feuds between them in Macedonia began during this period. The most respected among the numerous Serbian feudal lords of that time were the brothers Volkashin and Uglesha Mrnjavchevich.

Volkashin – King Marko’s father – occupied various positions in Dushan’s state: he was a head of a tribal state in Prilep, and late became a high courtier and a despot. In about 1365, he proclaimed himself a Tsar and thus became a co-ruler with the Tsar Urosh. His brother, the despot Uglesha ruled over the Struma region. Both brothers were killed in 1371 at Chernomen (Thrace), during the Marica battle against the Turks, in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent further penetration by the Turks into the Balkan Peninsula and forestall the direct danger of Turkish occupation of their territories. This defeat began the lose of independence held by the feudal rulers of Bulgaria, Serbia and Macedonia. By the end of the 14th century, the Turks had subjected Macedonia to their direct authority. It was the beginning of five centuries of slavery for the Macedonians under the Turks.

After the death of Volkashin, his eldest son Marko inherited the throne and title of his father. He was, however, forced to recognize Turkish authority, as supreme, to take an obligation before the Sultan to pay tribute (jizia and poll-tax) and to provide military assistance whenever so requested by the Sultan. The other Turkish vassals, like Konstantin Dragash or the Serbian despot Stefan Lazarevich (after the battle at Kosovo), had similar obligations.

The territory of Marko’s state stretched on the right bank of the River Vardar: from the mountain of Shar and Albanian mountains in the northeast, to Kostur (Kastoria) in the southwest, with its capital in Prilep. Skopje and Ohrid did not belong to Marko, except perhaps temporanly. As a king, Marko minted coins with the inscription: “King Marko faithful to Lord Jesus Christ.” A similar inscription is found on the frescoes depicling his figure in the monastery of St. Dimitar in Varosh, Prilep. In the Prizren (Serbia) church of the Introduction of the Holy Virgin, an inscription is found where Marko is named as “a young king.” Fulfilling his vassal obligation for military assistance to Sultan Bayazit, King Marko was killed on May 17, 1395 in Craiova (Romania) during the battle against the Vlach military leader Mircho. Other vassals of Sultan Bayazit also took part in the battle: the despot Stefan Lazarevich and Konstantin Dragash, who was also killed at the battlefield.

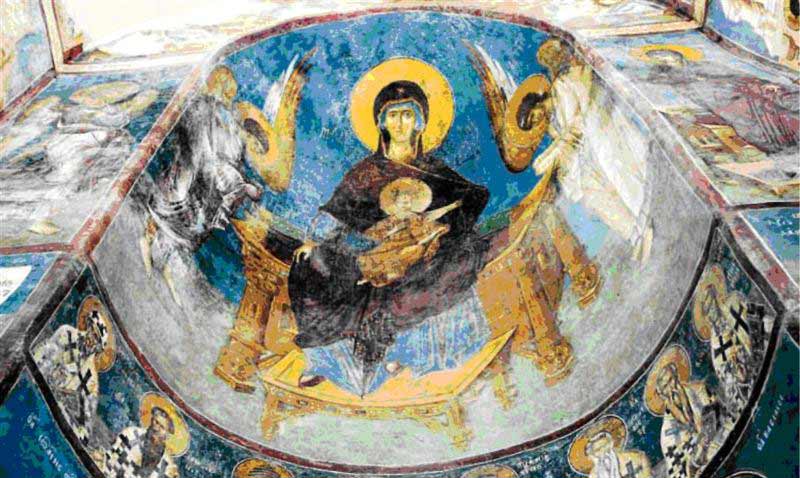

The Salutation of newborn Jesus by the three Wisemen of the East, Markov Manastir, Skopje, 14th century. The Construction of the monastery was initiated by Volkashin 1345, Krali Marko’s father, and finished by Krali Marko himself.

The preserved frescoes in St. Dimitriya church, Marko’s Monastery, Skopje, Macedonia, also speak about the in dependence of the brothers Volkashin and Uglesha. In Marko’s monastery near Skopje, “King Marko” is presented in king’s clothes in all his dignity, and also with the curved metallic horn decorated with ornaments and pearls which advanced the new dynasty. The intention was to emphasize not only the independence, but also the differences from the Nemagnich dynasty. It was shown not only by the absence of the saints from the Nemagnich circle who had incarnated the Serbian church and historical tradition (St. Simeon, Nemagna and St. Sava) but also by the presence of St. Clement of Ohrid among the holy fathers. By that, a clear distinction was made between the Serbian Patriarchate of Pec (which supported the duke Lazar) and the Archbishopric of Ohrid (which stood behind King Marko and his state.)

In connection with this is also the creation of the new dynasty. The proclamation of King Marko as a young king in a situation when the Tsar Urosh (like the tyrant Uglesha) had no legal successor, has already predetermined the king’s crown to Marko and the legitimacy or the separate dynasty – especially when Volkashin ended the co-ruler status and proclaimed himself to be independent and the sole sovereign of his state.

The reaction on the Nemagnich dynasty to the crowning of Volkashin and his declared independence is understandable and logical. That’s why in that tradition King Volkashin, although a victim of the fight against the Turk, remained a damned usurper. All of this was also the result of intention which is not mentioned very often.

In 1369, the decisive Kosovo battle took place between the two dynasties: Lazar I Irebeglanovic, Nikola Altomanovich and the Tsar Urosh. That is, the Nemagnich dynasty on one side and the brothers King Volkashin (probably together with the young successor Marko) and Tyrant Uglesha – the new “Mrgnavchevich” dynasty – on the other. The southern rulers won the battle and as cited they even took Tsar Urosh prisoner. Details are missing, and the sources are greatly lacking, but the event has historical importance. Although according to the Serbian tradition Tsar Urosh was considered to have been killed by King Volkashin, recent data points to the fact that he lived longer than Volkashin. However, as R. Mirkhaljchich says, Tsar Urosh become “a Tsar without empire, a sovereign without sovereignty,” without the support of the Romeyes and without the legitimacy of the Patriarchate of Pec, already in schism at that time. The brothers Volkashin and Uglesha, thanks to the size of the territories they governed and the supplied legitimacy of the Archbishopric of Ohrid (with the support of the Ecumenical Patriarchate) became the strongest power. They were the only power which could oppose the invasion of the Turks.

Such relations were the logic by which the Serbian north did not take place in the Marica battle against the Turks (1371) and King Marko did not take place in the Kosovo battle in 1389. It was a state and church antagonism between two dynasties which perhaps had no expressive national character but in which basis – as Misirkov also thinks – probably was the cultural and historical difference between the north and the south. It is not exactly known when and where Marko was crowned, but it was probably immediately after the Marica battle and his father’s death. Literally and legally, Marko might be considered as a co-ruler of the still living Tsar Urosh. Taking into consideration the ending of the Nemagnich dynasty, Marko should be considered to be the sole legitimate king of Serbia. But the real situation was probably different. In fact, King Marko was sovereign of the new Mrgnavchevich dynasty, if this name can also be confirmed by more trustworthy sources – because, as we are now informed, nowhere in the contemporary sources is the surname of Mrgnavchevich fixed. By the way, the name of the founder of this dynasty in Macedonia in the previous sources is found in Slovenian in the form ofKing Volkashin (without the suffix Stephen), while in the Dubrovnik documents in Latin he is recorded as Regis Volcassini, dominus rex Volkasinus.

Until now no official document, no charter, nor any royal gold seal has been found -herein Marko is titled as Prince Marko — only as Young King or King Marko. The folk tradition in Macedonia has been responsible.

King Marko was born about 1335. The first time he is mentioned in a document is when he visited Dubrovnik as a delegate of Volkashin. His name is also mentioned in some notes and chronicles of his time as a son of Volkashin or, later, as a king. Thus, in a document dated 1370, Volkashin mentioned his sons Marko and Andrew and his wife Elena, about whom there is no other data available in the history.

From the more recent documentation, the structure of the Volkashin family appears. King Volkashin and Queen Elena (in the monasticism she is called Elisaveta, and in the folk tradition she is mostly known as Efrosima) had four sons (Marko, Andrew, Ivanish and Dimitrya-Mitrush) and an unknown number of daughters, of which only the name of Olivera is mentioned, married to Gjurgje Balshish. King Marko married the daughter of Radoslav Hlapen, and left her before the Marica battle. Later he probably married Teodora and after 1377, he gave her to his father-in-law Radoslav and brought back Radoslav’s daughter, “Marko’s first wife, Jelena. ” It is not known if Marko had a child and a successor. All this concerning the marriage relations of King Marko gave a base for folk tradition.

In general, these facts are the basic historical data about King Marko. There are some other opinions about Marko to be mentioned, found in the chronicles and histories. The Dubrovnik chroniclers (Orbinin, Lukarevich and others) had mentioned Marko as a successor of Volkashin and had recorded his death at Rovine as a Turkish vassal. The Serbian Patriarch Paisie, a 17th century biographer, in his work The Life of Tsar Urosh, does not mention Marko at all, which is strange when one considers the fact that the work was mainly based on folk tradition. Likewise, other 18th century chroniclers and historians did not attribute serious significance to Marko. On the contrary, some accused him of serving the Sultan and the Turks. Thus, in the Thronous geneaology (1791), he is even accused of bringing the Turks to the Balkan Peninsula. Jovan Rajich, in his History of the South Slavs (1794), criticized the folk cult of Marko. The opinion of the Bulgarian historian Paisie of Chilandar about King Marko is in no milder.

After the death of King Marko, his state was incorporated by the Turks within their contemtories, perhaps because he had no direct heir. Dimitar and Andrew were forced to leave the country. Dimitar went to Dubrovnik (about 1400) and from here he left for Hungary, where he entered the service of the King Sigmund; he died sometime after 1407.

The destiny of the queen – the mother Elena -and of Marko’s brothers gives a possibility for concluding some situations and relations of the states of both Volkashin and Uglesha. It is known that Queen Elena / Elisaveta, Marko and Andrew all minted their own coins. This suggests that they had separate finances, and separate state borders. In 1374 Queen Elena/Elisaveta sent her logothete Dabizhiv to Dubrovnik in connection with the silver deposits of Volkashin. Until 1377, she was still alive, and she was mentioned in an official document with a gold seal of her son Andrew in St. Andrew church near Matka. It is not known when and were they entered the monastic order, but her name is mentioned in a later document of St. Jovan Pretecha monastery.

Especially unclear are the relations of Marko toward his brothers that in 1385 Ivanish left Macedonia and joined the Zeta and Albanian powers in the battle against the Turks where he died. Other data indicates that Andrew, as “a prince” in the time of the Kosovo battle in 1389, built the St. Andrew church. However, more trustworthy sources are missing, preventing us from establishing who was the Andrews de Macedonia who on April 14, 1389 enrolled in Vienna University. We are sure that in the middle of 1394 the brothers Andrew and Dimitrya had already left Macedonia and reached Dubrovnik in order to take their share of their father’s deposit. On August 10, they took the money and left for Hungary, where they served the greatest enemy of the Turks, the Hungarian king Sigmund.

What later happened to Andrew is not known, but it is clear that in 1399 he was no longer alive as his brother Dimitrya came alone to Dubrovnik in order to take over the part of the deposits left to the already slain Marko.

Dimitrya (Mitrush) served King Sigmund until the beginning of the century as a castellan of the town of Vilagosh and as head of the Zarand tribal state. The task of researching Hungarian archives and finishing the discovery of the descendants of King Volkashin remains. It is known that from the four brothers (there is no data about the sisters) only Andrew left successors, and his son was father of the wife of the Bosnian feudal lord Stepan Kosach.

In any case, one of the most important questions is that about the vassalage of Marko. Although immediately after the Marica battle many territories from Volkashin’s and Uglesha’s states were occupied by neighboring Christian rulers, the kingdom of Marko had an independent status for a quarter of a century. Its borders were often disturbed by the Turks, sieges were laid even in Prilep and Bitola, slaves were taken and later sold on Crete; however, the people had a relatively peaceful life. This was reflected in the folk memory and expressed through folk creativity. It is written that after 1377 Marko became a vassal of Bayazit I, but without trustworthy proofs. It is known that Marko’s brothers, who were anti-Turkish, left Macedonia toward the middle of 1394 and joined the king of Hungary (Ivanish had been slain in the battle against the Turks nine years before). What was Marko’s status at that time and what was the reason for the split between the brothers ? It seems that the crucial events place in the winter of 1393 – 94 when Bayazit I decided to liquidate his Balkan vassals and to include their territories into the borders of the Ottoman Empire. He invited them one-by- one to a conference in Seres, intending to execute them there. But Bayazit I changed his mind; he allowed a part of them to go back, and with the others he went to Thessaly. In some sources it is cited that the vassals gave their word they would not stand for remaining vassals any longer and later that they divided themselves into two groups: one group accepted the vassal destiny. Yet the names of Marko and his, brothers are not mentioned. Was this political schism the period of the split between the brothers?

It is a historical fact that King Marko as a vassal went with Bayazit’s army to battle against the Vlach duke Mirche and was killed along with Konstantin Dragash at Rovine on May 17, 1395. Obviously the people could not accept such a destiny for their king. According to folk tradition, immediately before the battle Marko comprehended his dishonest position and said, “I am saying and begging God to help the Christians, even if I am among the first to die in this”.

It is very normal that certain entity, in accordance with its views on past and visions of present and future, have profiled and built the personality of King Marko in the national mind. Poor written documents have even more given way to fantasy and encouraged hopes of long occupied Orthodox Balkan Slavs. That is how it came to creating a myth of his character, who absorbed a great deal of characteristics of mythological and legendary characters of the Balkan and non-Balkan provenance. On the other hand, his circumstances of the centuries long position of the Macedonian people. Slavery and freedom, justice and force, antipodes of the cross and the crescent were also in question.

14th century represents a turning point in the history of the south Slavic and Balkan nations. It, in fact, was the end of one civilization period and beginning of another completely different period, which significantly changed the ethno-cultural map of the Balkan Peninsula, and to a large extent, Europe’s map. It was a historical moment of factual dissolution of a few powerful Christian kingdoms domination Balkan people were dominated by an ethnic and religiously different occupier. The fact itself, creates important presumptions for modulating the ideas pertaining to the King Marko among the south Slavic people, as their last legitimate Christian and Slavic sovereign and protector

Folklore tradition has been trying for two centuries now, to reveal the reasons taking into consideration that in the last years of his ruling, King Marko was an Ottoman vassal. Even Krste Misirkov, in his graduate study at Petersburg University in 1902, entitled as Approaching the Issue of the Nationality and Reasons for Popularity of the Macedonian King Marko, represents an interesting attempt for answering this question. However, final answer to this question has not been yet found Neither has science given the answer of a number of other issues concerning the multidimensional personality of Marko in the south Slavic, and, generally, Balkan folklore.

The character of King Marko is surely the most realistic among the people in Macedonia. It should not be forgotten that Prilep was his seat. The memory of him can be seen in the ma out Macedonia: Marko’s Towers in Prilep, where he was born, churches and monasteries with frescoes with his picture. His suggestive look on the frescoes had encouraged the Impressions on the last prominent Christian King in the country.

If we take in consideration all the presentations of the poetic figure of King Marko in Macedonian creative folk works — to be found in the poems, the legends and the oral traditions — then we see a figure of a hero who is not “without faults and fears,” as in fact every idealized “hero above heroes” should look. But he is a hero who is, first and foremost, a human being, like any other human being, having both positive and negative characteristics. Who has. almost equally, as many faults as he has virtues. It is obvious that the poetic figure of King Marko, in his centuries of development in the environment of the Macedonian people and in those of the other South Slavic peoples, was gradually changing shape in accordance with the living circumstances of the everyday people. In fact, it may be said that the most important good and bad sides of mankind have been incorporated in Marko’s personality. That is the reason why King Marko is such a controversial figure in our folk creative works and, at the same time, he is yet so close and understandable, even when some of his actions and deeds are normally unacceptable.

No matter that data concerning King Volkashin and King Marko are extremely uncertain and insufficient, it is undeniable that they emerge from the hierarchy of the Serbian feudal state, and in one period even, they used to be co-rulers of the Serbian throne. I’m not planning to elaborate the question of the ethnic character of the middle century states, including feudal Serbia, it is a historical fact that there were state formations in Macedonia in the second half of the 14th century, which were in many respects opposed to the north Serbian states, and were not close even with the Eastern Bulgarian kingdoms. There were separate regional interests which dictated this relation. It, however, was dictated by the former ethno-cultural development of the people who lived in this area. We are not talking about state formations which had the current ethno-name – Macedonian. It does not mean taking over someone else’s history Is not the parallel with the Ukrainians, Slovenians and Slovaks an indicating factor’s. In the historical sources often find ethno-names concerning Macedonians which identify us with the Romeis. Bulgarians, Serbs, and rarely. mainly in the last two countries we are represented as Macedonians.

THREEFOLD TYRANNY

In 1914 Dimitriya Chupovski, in his poem “King Marko”, call on Marko to awake and dash forward with his people against the “triple tyranny” by dividers and conquerors of his homeland Macedonia. Pointing out the strife and culture of the Macedonian people in a Memorandum sent to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs on behalf of the Macedonian colonies in Petersburg and Odessa, Chupovski, together with Krste Misirkov, inter alia emphasized: “We have an old and high local Macedonian culture, dating back from the times of the founders of Macedonian Slav education St. Clement, Naum and Gorazd, as well as from the period of the first Slav state – Tsar Samuil’s one, the second Dobromir Strezo’s state; and the third one – Kings Volkashin and Marko’s, and through the 19th century, particularly in its second half.

Virtual Macedonia

Republic of Macedonia Home Page

Here at Virtual Macedonia, we love everything about our country, Republic of Macedonia. We focus on topics relating to travel to Macedonia, Macedonian history, Macedonian Language, Macedonian Culture. Our goal is to help people learn more about the "Jewel of the Balkans- Macedonia" - See more at our About Us page.

Leave a comment || Signup for email || Facebook |

History || Culture || Travel || Politics