The long waves of penetration of the Slavs towards the end of the 7th century AD resulted in an entirely different situation – Macedonia acquired new inhabitants and became a Slav territory. The Sclavinia was their first form of social organization and structure. Then they fell under the Byzantine and Bulgarian empires. Following the fall of the Bulgarian Empire and the decline of the Byzantine Empire, Samuil, a skilled military leader and statesman, established the first Macedonian state (976-1018). Samuil’s Empire comprised the whole of Macedonia, Thessaly, Epirus, Albania and the former coastal Sclaviniae of Duklja, Travunja, Zahumlje and the Neretva region, and also Serbia (t.e. Rashka) and a considerable part of Bulgaria. In this large empire, the most numerous subjects were the Macedonian Slavs, the Slavs in Greece and Peloponnesus, and only then Bulgarians, followed by Serbs, Croats and finally Romaioi (Byzantines), Albanians and Vlachs.

Heading this conglomeration of people was Tsar Samuil, who was crowned by the Roman Pope, because Samuil was in a constant conflict with the Byzantine Empire, and the crown of the Bulgarian rules was in Constantinople. This crowning gave an international character and recognition to Samuil’s Empire. The attribute “Bulgarian” is explained by the practice of the Roman Pope to give a title to the crown which was identified with the territory of an already recognized empire, and Samuil’s Empire extended over the territory of the Bulgarian Empire which has collapsed.

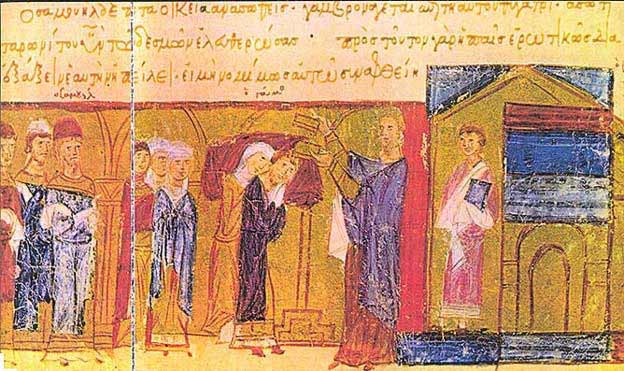

Samuil had a crown, secretaries and bureaucracy; there was an emperor’s office issuing documents. The official language in Samuil’s Empire was Slavonic, although as a diplomatic language of the court Greek was also used. The Archbishopric of Ohrid was established at the time of Samuil, and Ohrid became the religious centre and the capital of the Empire.

Following the final subjugation of Samuil’s state in 1018, the Byzantine Empire dealt fiercely with the Macedonian population, particularly those living in the towns: they were banished and aliens were brought in their place. The Byzantine Empire also placed the Archbishopric of Ohrid under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchstate of Constantinople, and the Greek hierarchs started suppressing Slavonic written documents, Slav hagiographies, etc. It was considered that with the eradication of the Archbishopric of Ohrid the traditions cherished by the Macedonian people would also be eradicated.

A historical map of Samuil’s medieval empire during the greatest territorial expansion on the Balkan Peninsula in 996.

Yet Slavonic literacy could not be eradicated. The extraordinary work of the educators Cyril and Methodius had a firm basis. As well as creating the first Slavonic alphabet (Glagolitic), translating the basis religious service books from the Greek into the language spoken by the Macedonian Slavs in the surroundings of Salonika and establishing Old Slavonic literature, Cyril and Methodius also expanded their activity among other Slavs.

Clement and Naum continued the mission of the Salonika brothers. In Ohrid, during his activity of 20 years, Clement instructed about 3,500 teachers and priests in the Slavonic alphabet and introduced the Slavonic language in religious service. He was the first original Slav and Macedonian writer. The Ohrid Literary School, being the first Slav university, has left deep traces and has been the basis for Macedonian cultural identity.

Origin and Ethnicity of Czar Samuil

The historical chart of the Ohrid autocephalous Patriarchate (Archbishopric) jurisdiction in the reign of Tsar Samuil and after his death (until 1020)

Nothing definite is known about the early history of the Cometopuli. The contemporary Armenian historian Stephen of Taron (Asolik), trans. Gelzer and Burckhardt (1907), 185 f., says that they were of Armenian descent. In spite of N. Adontz, ‘Samuel l’Armenien’ 3 ff., it remains doubtful how much weight can be given to the statement of this Armenian historian whose information on Samuil is full of obvious errors. N. P. Blegmv, ‘Bratjata David, Moisej, Aaron i Samuil’ (The brothers David, Moses, Aaron and Samuel), Godisnik na Sofijsk. Univ., Jurid. Fak. 37, 14 (1941-2), 28 ff., considers that Count Nicholas was a descendant of the proto-Bulgar Asparuch, and his wife Ripsimia, the mother of the Cometopuli, a daughter of the czar Symeon, which is entirely without foundation. His ‘Teorijata za Zapadno bulgarsko carstvo’ (Theories on the West Bulgarian Empire), ibid. 16 ff., contains equally fantastic views.

The history of the origin of Samuil’s empire is a much debated question. Scholars no longer support Drinov’s theory of a West Bulgarian empire of the Sigmanids founded in 963, and today two different and conflicting views are current. One view holds that by 969 a West Bulgarian (Macedonian) kingdom under the Cometopuli had split off from the empire of the tzar Peter and that this existed independently side by side with the East Bulgarian empire (on the Danube) ; further, they consider that it was on the eastern part which was conquered by Tzimisces, while the western part continued and formed the nucleus of Samuel’s empire. The second view, worked out in detail by D. Anastasijevic, ‘L’hypothese de la Bulgaric Occidentale’, Recueil Uspenskij I (1930), 20 ff., insists that there was no separation between an eastern and western Bulgaria, and that Tzimisces conquered the whole of Bulgaria which only regained its independence with the Cometopuli’s revolt in 976 and the foundation of a new empire in Macedonia. This latter interpretation seems to me to be in the main correct, though both theories appear to go astray in so far as they imply that the subjection of the country took the form of a regular occupation of the whole countryside. Anastasijevic rightly emphasizes that the sources give practically no ground for the assumption that an independent West Bulgaria ever existed side by side with an East Bulgaria, and they afford equally slight evidence for the statement that there was a revolt of the Cometopuli before 976. The frequently quoted statement in Scylitzes-Cedren. II, 347, dated rather arbitrarily to the year 969 and equally arbitrarily regarded as an account of a revolt of the Cometopuli said to have broken out in this year, is in reality only a casual comment, by way of an aside, which anticipates the events it refers to (cf. the doubts of Runciman, Bulgarian Empire 218, and Adontz, ‘Samuel I’Armenien’, 5 ff.). On the other hand, the sources make it quite clear that Tzimisces-like Sviatoslav-never set foot in Macedonia (the entirely unsupported statement of the later Priest of Dioclea who says that Tzimisces took possession of Serbia, and consequently Macedonia as well, is of no importance). The capture of the capital and the deposition of the ruler signified the subjection of the country without any need to conquer its territory inch by inch. It is, however, true that control which was limited to occupying the centre could in certain circumstances easily be overthrown from the periphery, and this was in fact what happened after the death of John Tzimisces and the outbreak of internal conflicts in Byzantium. This problem has been recently discussed by Litavrin, Bolgarya i Vizantija 26 I ff., who does not, however, advance any new or compelling arguments for the view he adopts, i.e. that ‘Bulgaria continued its existence in the West’. He concludes: ‘The period from 969 to 976 was in Western Bulgaria a time when its forces were consolidated under the rule of the Cometopuli. . . .’ But, as our observations above make clear, this assertion has not the slightest foundation in the sources.

Virtual Macedonia

Republic of Macedonia Home Page

Here at Virtual Macedonia, we love everything about our country, Republic of Macedonia. We focus on topics relating to travel to Macedonia, Macedonian history, Macedonian Language, Macedonian Culture. Our goal is to help people learn more about the "Jewel of the Balkans- Macedonia" - See more at our About Us page.

Leave a comment || Signup for email || Facebook |

History || Culture || Travel || Politics

if what you say is supported by these maps, why Macedonia is the only one marked as REGION? It is italic and vertical, while countries are in horizontal + bold. Just saying 🙂

This is false historical information, relying on absolutely no historical facts, and the bit of true information has been altered with the idea of twisting the truth and lying about the existence of the Macedonian nation and people.

Plus it is practically impossible because every historian knows that as far back as Roman times, Roman authors and historians say that the lands from the Danube River to Thessalonica were inhabited by Thracians, Getae and Dacians. As absolutely nowhere there is talk of Macedonians in these lands.

Тhe name of the geographical area has absolutely nothing to do with the people and history especially with the rulers.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_of_Bulgaria

Read the true history about Samuil of Bulgaria. If you don’t believe it ask greek historics.