Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), the king of Macedonia that conquered the Persian empire and annexed it to Macedonia, is considered one of the greatest military geniuses of all times. He is the first king to be called “the Great.”

Table of Contents

Early Life

Alexander is supposed to have been fair skinned, with a ruddy tinge to his face and chest. Plutarch stated that he had a pleasing scent. Like all Macedonians, Alexander liked his liquor, but his fondness for wine also caused some of his outbursts of rage. Alexander liked drama, the flute and the lyre, poetry and hunting, but what he truly wanted in his life, was a glory and valor, rather than easy living and riches. He was not fond of athletic contests, according to Plutarch.

Alexander, born in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia, was the son of Philip II, king of Macedonia, and of Olympia, a princess of Epirus. Philip and Olympia wanted nothing less than the best for their son, so when he was 13, his parents hired Aristotle to be his personal tutor. Alexander was trained together with other children of the nobility at Aristotles Nyphaeon. It is here that Alexander met Hephastion, his future best friend and alter ego. Aristotle gave Alexander a thorough training in rhetoric and literature and stimulated his interest in science, medicine, and philosophy, all of which became of the utmost importance for Alexander in his later life. The two later became estranged, due to their difference of opinion on the status of foreigners; Aristotle saw them as barbarians, while Alexander sought to unite Macedonians and foreigners.

In 340 BC, when Philip went to Byzantium to fight rebels, Alexander, a mere 16 years old, was left in charge of Macedonia as regent, with the power to rule in Philip’s name in his absence. That Alexander was given such a position at such a young age indicates that he was already accomplished in battle. But Alexander never got along well with his father, although Philip was proud of Alexander for the Bucephalus incident. Alexander had always been closer to Olympia than to Philip. Philip and Olympia also did not get along all that well, owing primarily to Olympia’s non-Macedonian heritage.

Olympia, mother of Alexander the Great

Philip II of Macedonia, father of Alexander the Great

The family essentially was split apart irreparably when Philip married a woman named Cleopatra, a Macedonian. At the wedding banquet, Cleopatra’s father made a remark about Philip fathering a “legitimate” heir, i.e., one that was pure Macedonian. Alexander took exception and threw his cup at the man, and some sources say Alexander killed him. Enraged, Philip stood up and charged at Alexander, only to trip and fall on his face in his drunken stupor. Alexander, rather upset at the scene, is to have shouted:

“Here is the man who was making ready to cross from Europe to Asia, and who cannot even cross from one table to another without losing his balance.”

When Philip divorced Olympia Alexander fled. Although allowed to return, he remained isolated until Philip was assassinated (some think that Olympia may have even had a role in Philip’s murder), in the summer of 336 BC.

Alexander on the Macedonian throne

Alexander ascended to the Macedonian throne when his father died. Once in power, he disposed quickly of all conspirators and domestic enemies by ordering their execution. Then he descended on Thessaly, where partisans of independence had gained ascendancy, and restored Macedonian rule. Before the end of the summer of 336 BC he had reestablished his position in Greece and was elected by a congress of states at Corinth.

But, Greek cities, like Athens and Thebes, which had pledged allegiance to Philip, were unsure if they wished to do the same for a twenty-year-old boy. Moreover, the Hellenes considered Macedonian domination in the Greek states as an alien rule, imported from outside by the members of other tribes, the, as Plutarch says, allophyloi (Plutarchus, Vita Arati, 16). Likewise, northern barbarians that Philip had subdued were threatening to break away from Macedonia and wreak havoc in the north. Alexander’s advisors suggested that he let Athens and Thebes go and to be gentle with the barbarians to prevent a revolt. However, in 335 BC, Alexander campaigned toward the Danube, to secure Macedonia’s northern frontier. He carried out a successful campaign against the defecting Thracians, penetrating to the Danube River. Alexander marched quickly north and drove the rebelling barbarians beyond the Danube River and out of the way. On his return he crushed in a single week the threatening Illyrians.

On rumors of his death, a revolt broke out in Greece with the support of leading Athenians. Alexander marched south covering 240 miles in two weeks. Arrian related the story of how Alexander dealt with Thebes and Athens. There were rumors in these cities that Alexander had been killed, and that the time was right for them to separate themselves from Macedonia. Instead, in the fall of 335 BC, Alexander marched up to the gates of Thebes, and let them know that it was not too late for them to change their minds. The Thebans responded with a small contingent of soldiers, which Alexander repelled with archers and light infantrymen. The next day, Alexander’s general, Perdiccas, attacked the gates. Perdiccas broke through and into the city, and Alexander moved the rest of his force in behind to prevent the Thebans from cutting Perdiccas off from the rest. The Macedonians then stormed the city, killing almost everyone in sight, women and children included. They plundered, sacked, burned and razed Thebes, as an example to the rest of Greece. Only the temples and the house of the poet Pindar were spared from distraction. Athens then quickly rethought its decision to abandon Alexander. Greece remained under Macedonian control.

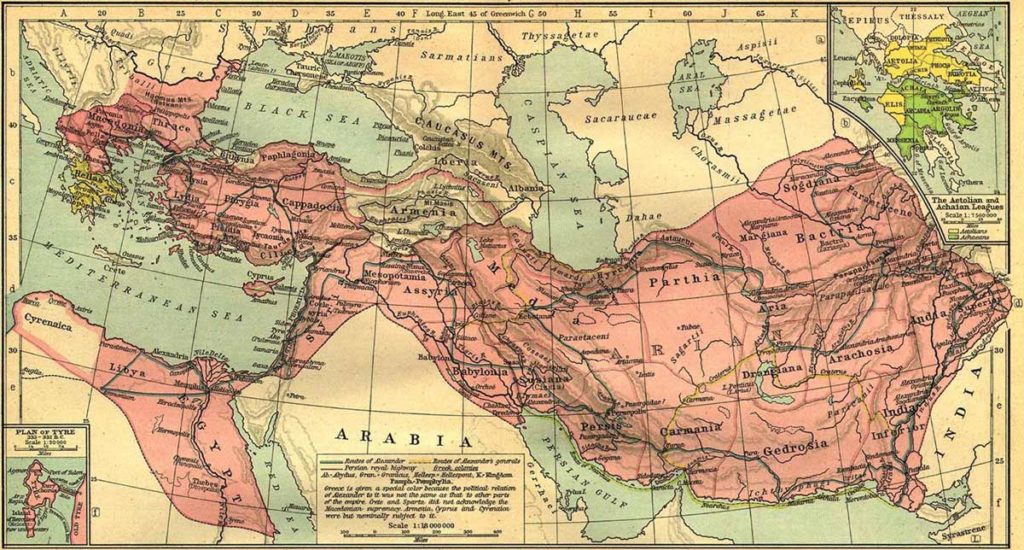

The battles of Granicus and Issus

Alexander began his war against Persia in the spring of 334 BC by crossing the Hellespont (modern Dardanelles) with an army of 35,000 Macedonians and 7,600 Greeks. He threw his spear from his ship to the coast and it stuck in the ground. He stepped onto the shore, pulled his weapon from the soil, and declared that the whole of Asia would be won by the spear. His chief officers, all Macedonians, included Antigonus, Ptolemy, and Seleucus.

The Macedonian army soon encountered the Persian army under King Darius III at the crossing of the river Granicus, near the ancient city of Troy. Alexander attacked an army of Persians and Greek hoplites (a heavily armed foot soldiers of ancient Greece) who distinguished themselves on the side of the Persians against the Macedonians. Alexander’s forces defeated the enemy (totaling 40,000 men) and, according to tradition, lost only 110 men.

Then he turned northward to Gordion, home of the famous Gordian Knot. The legend behind the ancient knot was that the man who could untie it was destined to rule the entire world. Alexander simply slashed the knot with his sword and unraveled it.

Continuing to advance southward, in November of 333 BC, Alexander met Darius in battle for the second time at a mountain pass at Issus, in northeastern Syria. The size of Darius’s army is unknown but although the Persian army greatly outnumbered the Macedonians, the narrow field of battle allowed Alexander to defeat the Persians. The Battle of Issus ended in a great victory for Alexander. Cut off from his base, Darius fled northward, abandoning his mother, wife, and children to Alexander, who treated them with the respect due to royalty.

In the next year, he marched down the Phoenician coast and received the surrenders of all of the major cities there except for Tyre. A seven-month siege of the city followed, and the Tyrians eventually surrendered to Alexander. Then he continued south into Egypt after he had secured the entire Aegean coast.

Alexander in Egypt

Alexander entered Egypt in 331 BC. When he arrived, he was welcomed, and he ordered a city to be designed and founded in his name at the mouth of the river Nile. Alexandria would become one of the major cultural centers in the Mediterranean world in the following centuries.

In the spring of 331 Alexander made a pilgrimage to the great temple and oracle of Amon-Ra, Egyptian god of the sun, whom the Greeks identified with Zeus. The earlier Egyptian pharaohs were believed to be sons of Amon-Ra and Alexander, the new ruler of Egypt, wanted the god to acknowledge him as his son. The pilgrimage apparently was successful, and it may have confirmed in him a belief in his own divine origin.

While in Egypt, Alexander spontaneously decided to make the dangerous trip across the desert to visit the oracle at the temple of Zeus Ammon. On the way, he was blessed with abundant rain, and he was guided across the desert by ravens. At the temple, Alexander spoke to the oracle about matters that are unclear to most historians. Many sources, however, speculated that the priest told Alexander that he was the son of Zeus Ammon and that he was destined to rule the world.

He was then made pharaoh voluntarily by the Egyptians, who despised living under Persian rule. He exchanged letters with Darius while he was in Egypt, and the Persian offered a truce with Alexander with a gift of several western provinces of the Persian Empire, but Alexander refused to make peace unless he could have the whole empire. In the middle of 331 BC Alexander marched back to Persia to find Darius.

The end of the Persian empire

Alexander reorganized his forces at Tyre and started for Babylon with an army of 40,000 infantry and 7000 cavalry. He conquered the lands between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and found the Persian army which, according to the exaggerated accounts of antiquity, was said to number a million men at the plains of Gaugamela (near modern Irbil, Iraq). The Macedonians spotted the lights from Persian campfires one night, and they encouraged Alexander to lead his attack under cover of darkness. He refused to take advantage of their situation because he wanted to defeat Darius in an equally matched battle so that the Persian king would never again dare to raise an army against the Macedonians. The two armies met on the battlefield the next morning on October 1, 331 BC, and the Macedonian forces swept through the Persian army and slaughtered them. Darius fled as he had done at Issus to the mountain residence of Ecbatana, while Alexander occupied Babylon, the imperial capital Susa, and Persepolis. Henceforth, Alexander was proclaimed king of Persia, and to win the support of the Persian aristocracy he appointed mainly Persians as provincial governors. After four months, the Macedonians burned the royal palace to the ground thus completing the end of the ancient Persian Empire.

Yet a major uprising in Greece had Alexander so deeply worried, that after hearing that the rebellion had failed, he proclaimed the end of the Hellenic Crusade and discharged the all Greek forces.

Alexander continued his pursuit of Darius for hundreds of miles from Persepolis. When he finally caught up to him, he found the Persian king dead in his coach, assassinated by his own men. Alexander had the assassin executed and gave Darius a royal funeral.

Macedonian nobles resistance and the Macedonian language

During the reign of Alexander the Great, the Macedonians spoke their own native language, as the native language language of Alexander the Great was not understood by the ancient Greeks (Quintus Curtius Rufus, VI, 9, 37 ). Similarly, Plutarch points out that Alexander spoke to his fellow countrymen in Macedonian: “he [Alexander] called out aloud to his guards in the Macedonian language, which was a certain sign of some great disturbance in him” (Plutarch, Alexander, 51). Still, Alexander spoke also Greek, loved Homer, and respected his tutor Aristotle. At the same time though, there is much evidence that generally he was not fond of the Greeks of his day. The chronicler Curtius, describing the atmosphere before a battle, gave a notion of the different attitudes of the great commander, who psychognostically applied the principle of identity to every ethnic group in his army. In respect to the various motives for taking part in that war, Curtius wrote:

“Riding to the front line he [Alexander the Great] named the soldiers and they responded from spot to spot where they were lined up. The Macedonians, who had won so many battles in Europe and set off to invade Asia … got encouragement from him – he reminded them of their permanent values. They were the world’s liberators and one day they would pass the frontiers set by Hercules and Patter Liber. They would subdue all races on Earth. Bactrius and India would become Macedonian provinces. Getting closer to the Greeks, he reminded them that those were the people who provoked war with Greece, … those were the people that burned their temples and cities … As the Illirians and Trakians lived mainly from plunder, he told them to look at the enemy line glittering in gold …”

Q. C. Rufus, Alexander III, 10, 4-10

After all, he thoroughly destroyed Thebes. Therefore, his empire is correctly called Macedonian, not Greek, for he won it with an army of 35,000 Macedonians and only 7,600 Greeks.

Alexander’s increasingly Oriental behavior led to trouble with Macedonian nobles and some Greeks. In 330 BC a series of allegations was brought against some of Alexander’s officers concerning a plot to murder him. Alexander tortured and executed his friend, Philotas (commander of the cavalry) the accused leader of the conspiracy, and several other high-ranking officials in order to eliminate the possibility of an attempt on his life. The question of the use of the ancient Macedonian language was raised by Alexander himself during the trial of Philotas. Alexander has said to Philotas:

“‘The Macedonians are about to pass judgment upon you; I wish to know whether you will use their native tongue in addressing them.’ Philotas replied: ‘Besides the Macedonians there are many present who, I think, will more easily understand what I shall say if I use the same language which you have employed.’ Than said the king: ‘Do you not see how Philotas loathes even the language of his fatherland? For he alone disdains to learn it. But let him by all means speak in whatever way he desires, provided that you remember that he holds out customs in as much abhorrence as our language.'”

Quintus Curtius Rufus, Alexander, VI. ix. 34-36

The trial of Philotas took place in Asia before a multiethnic public, which has accepted Greek as their common language. Alexander spoke Macedonian with his conationals, but used Greek in addressing West Asians. Like Illirian and Tracian, ancient Macedonian was not recorded in writing. However, on the bases of about a hundred glosses, Macedonian words noted and explained by Greek writers, some place names from Macedonia, and a few names of individuals, most scholars believe that ancient Macedonian was a separate Indo-European language. Evidence from phonology indicates that the ancient Macedonian language was distinct from ancient Greek and closer to the Tracian and Illirian languages.

Another old-fashioned noble, Cleitus, was killed by Alexander himself in a drunken brawl. Heavy drinking was a cherished tradition at the Macedonian court when Alexander ran him through with a spear. Although he mourned his friend excessively and nearly committed suicide when he realized what he had done, all of Alexander’s associates thereafter feared his paranoia and dangerous temper. Alexander next demanded that Europeans follow the Oriental etiquette of prostrating themselves before the king – which he knew was regarded as an act of worship by Greeks. But resistance by Macedonian officers and by the Greek Callisthenes (a nephew of Aristotle who had joined the expedition as the official historian of the crusade) defeated the attempt. The Greek Callisthenes was soon executed on a charge of conspiracy.

As the Macedonians marched into Parthia, the tone of the journey changed. Alexander had adopted the Persian style of dress, rather than his traditional Macedonian clothing, and his troops were unhappy with him. After all, up until that point, the Macedonian soldiers respected him immensely, as they saw him as a partner working for the common good of all Macedonians, the nobles and the masses. He was well known for calling on his fellow countrymen to join him in battle by their own will:

“However he told them he would keep none of them with him against their will, they might go if they pleased; he should merely enter his protest, that when on his way to make the Macedonians the masters of the world, he was left alone with a few friends and volunteers. This is almost word for word as he wrote in a letter to Antipater, where he adds, that when he had thus spoken to them, they all cried out, they would go along with him whithersoever it was his pleasure to lead them.”

Alexander in India

In the spring of 327 BC, Alexander and his army marched into India invading Punjab as far as the river Hyphasis (modern Beas). At this point the Macedonians rebelled and refused to go farther.

The greatest of Alexander’s battles in India was against Porus, one of the most powerful Indian leaders, at the river Hydaspes. On July 326 BC, Alexander’s army crossed the heavily defended river in dramatic fashion during a violent thunderstorm to meet Porus’ forces. The Indians were defeated in a fierce battle, even though they fought with elephants, which the Macedonians had never before seen. Alexander captured Porus and, like the other local rulers he had defeated, allowed him to continue to govern his territory. Alexander even subdued an independent province and granted it to Porus as a gift.

In this battle Alexander’s horse, Bucephalus, was wounded and died. Alexander had ridden Bucephalus into every one of his battles in Greece and Asia, so when it died, he was grief-stricken and founded a city in his horse’s name.

Alexander’s next goal was to reach the to travel south down the rivers Hydaspes and Indus so that they might reach the Ocean on the southern edge of the world. The army rode down the rivers on the rivers on rafts and stopped to attack and subdue villages along the way. During this trip, Alexander sought out the Indian philosophers, the Brahmins, who were famous for their wisdom, and debated them on philosophical issues. He became legendary for centuries in India for being both a wise philosopher and a fearless conqueror.

One of the villages in which the army stopped belonged to the Malli, who were said to be one of the most warlike of the Indian tribes. Alexander was wounded several times in this attack, most seriously when an arrow pierced his breastplate and his ribcage. The Macedonian officers rescued him in a narrow escape from the village. Alexander and his army reached the mouth of the Indus in July 325 BC and turned westward for home.

Alexander’s marriage

In the spring of 324, Alexander held a great victory celebration at Susa. He and 80 close associates married Iranian noblewomen. In addition, he legitimized previous so-called marriages between soldiers and native women and gave them rich wedding gifts, no doubt to encourage such unions. When he discharged the disabled Macedonian veterans a little later, after defeating a mutiny by the estranged and exasperated Macedonian army, they had to leave their wives and children with him. Because national prejudices had prevented the unification of his empire, his aim was apparently to prepare a long-term solution (he was only 32) by breeding a new body of high nobles of mixed blood and also creating the core of a royal army attached only to himself. After his death, nearly all the noble Susa marriages were dissolved. He established training programs to teach Persians about Greek and Macedonian culture, and he married Roxane, a Persian.

Alexander’s death

We will probably never know the truth, of Alexander’s mysterious death, even though new theories are still coming out. Alexander the Great, the Macedonian king and the great conqueror, died at the age of 33, on June 10, 323 BC. Three days earlier, on the 7th of June, 323 BC, the Macedonians were allowed to file past their leader for the last time before he finally succumbed to the illness. Alexander died without designating a successor. His death opened the anarchic age of the Diadochi and the Macedonian Empire will eventually cease to exist.

Virtual Macedonia

Republic of Macedonia Home Page

Here at Virtual Macedonia, we love everything about our country, Republic of Macedonia. We focus on topics relating to travel to Macedonia, Macedonian history, Macedonian Language, Macedonian Culture. Our goal is to help people learn more about the "Jewel of the Balkans- Macedonia" - See more at our About Us page.

Leave a comment || Signup for email || Facebook |

History || Culture || Travel || Politics